For a while, my workflow with AI looked like everyone else’s.

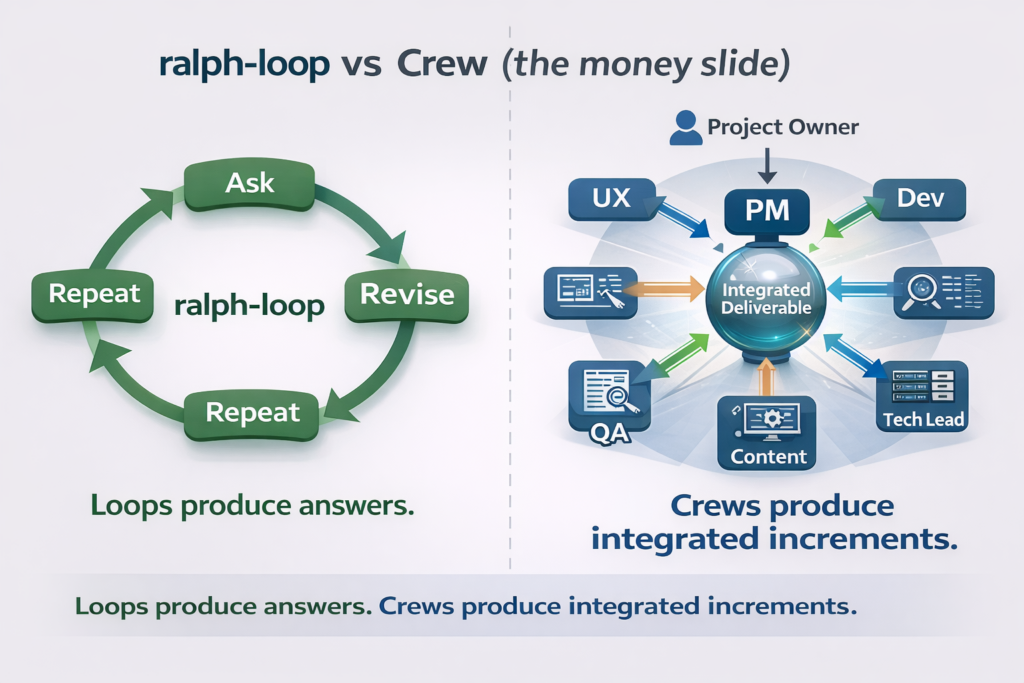

Ask for a feature. Get an answer. Refine it. Ship it. Fix what breaks. Repeat.

It’s the classic loop, it’s called the ralph-loop: one plugin, one model, one thread, one endless iteration. And to be fair, it’s great when the task is small and contained: a function, a refactor, a UI component, a prompt rewrite.

But OtterForm isn’t a single task. It’s a product.

And products don’t fail because you couldn’t write code. They fail because you ship almost-right decisions: unclear requirements, missing edge cases, messy UX, weak error handling, copy that confuses users, and “we’ll add tests later” that becomes “we’ll regret this forever.”

At some point I realized something simple:

I didn’t need a smarter loop. I needed a team.

So I stopped treating AI like a vending machine and started treating it like an organization: a Crew.

Not multiple “characters.” A real delivery structure: roles, responsibilities, quality gates, and someone accountable for integration.

The moment the ralph-loop shows its limits

The ralph-loop breaks the moment you ask something like:

- “Improve the form builder UX.”

- “Make embedding dead simple.”

- “Reduce support tickets from edge cases.”

- “Make it feel premium, not just functional.”

A single agent can attempt all of those at once, but the output tends to blur:

- UX suggestions that ignore engineering constraints

- code that works but isn’t testable

- copy that reads fine but doesn’t match the UI state

- decisions that don’t survive the real world (Safari, mobile browsers, slow networks, messy inputs)

The loop produces answers. What you actually need is delivery.

What changed when I let Claude build a crew

The Crew model is, in principle, simple:

- One Project Manager (PM) is the only interface to me.

- The PM can spawn specialists on demand: UI/UX, Architect, Developer, QA, DevOps, Content (and “externanal” consultants if needed).

- Everyone reports to the PM.

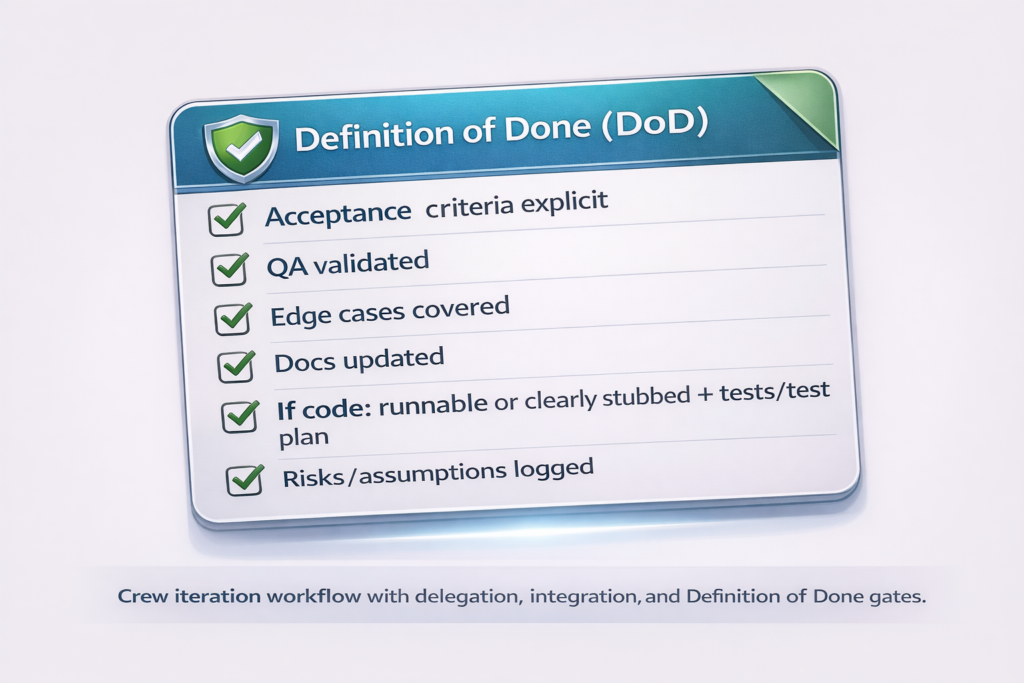

- The PM integrates everything into a single coherent increment and enforces a Definition of Done.

That’s the entire trick.

It’s the same reason real teams outperform brilliant individuals: specialization + verification + integration.

This is also why the “dynamic crew” prompt matters: it gives the PM the authority to create the right experts when the project demands it, instead of pretending one loop can be an architect, designer, tester, and copywriter simultaneously.

I’ve written before about using Claude as a sparring partner for building projects (including AI SNAKE, where AI helped with logic, debugging, and docs) but, the Crew approach is a step beyond “sparring partner.” It’s structured collaboration.

Two OtterForm examples of how a crew builds better than a loop

I’ll keep these examples intentionally “clean”: no proprietary internals, no secret sauce: just the way the workflow plays out.

Example 1: The Form Builder UX That Feels Fast (Not Just “Has Features”)

The ask sounds innocent: “Make the builder faster.”

In a ralph-loop, you often get a grab bag:

- “Add keyboard shortcuts”

- “Add inline editing”

- “Add a command palette”

- “Add autosave”

- “Add undo/redo”

All good ideas. But the loop usually won’t do the hard part: define what fast means, decide what to ship first, and test it like a product.

In a Crew, the PM forces clarity.

Before anyone writes code, the PM translates “faster” into acceptance criteria like:

- Create a question in under X seconds using keyboard only

- No accidental deletes without undo

- Edits are visible immediately in preview

- Works consistently on Chrome/Safari and mobile browser usage (where relevant)

- Empty states and error states are understandable

Then the PM delegates:

- UI/UX designs the interaction model (what is clickable, what is editable in place, what is a modal, what is instant).

- Developer implements the smallest slice first (one shortcut, one inline-edit path, one preview behavior).

- QA tries to break it: rapid edits, undo edge cases, weird inputs, keyboard-only, focus traps.

- Content writes the microcopy that prevents confusion (“Press Enter to save”, “Esc to cancel”, “Changes saved”).

- PM merges everything into a single deliverable: not “ideas,” but a shipped UX increment with a checklist.

The outcome isn’t just “more features.” It’s a builder that feels fast because the team aligned the UX, implementation, and validation around the same definition of done.

That alignment is exactly what the ralph-loop struggles to produce consistently.

Example 2: embedding that doesn’t become a support nightmare

Embedding sounds like a developer detail. It isn’t. It’s an adoption feature.

With a ralph-loop, you can absolutely generate an embed snippet and call it a day. Then reality shows up:

- a client site has a strict CSP

- a theme breaks layout

- Safari behaves differently

- the snippet loads slowly on a heavy page

- users don’t understand which option to pick (inline vs popup vs link)

A Crew treats embed as a cross-functional slice.

The PM frames it like a product story:

- “A user should embed an OtterForm form in under 2 minutes”

- “It should work on common stacks without surprising conflicts”

- “Instructions should be clear to non-developers”

- “We can track whether embeds succeed (without being creepy about it)”

Then:

- Architect flags constraints and tradeoffs (compatibility, security posture, performance implications).

- Developer implements the simplest robust embed path first.

- QA tests it across browsers and basic environments (static HTML, common CMS pages, mobile browsers).

- Content produces the actual embed instructions people follow: short, scannable, with “if this happens, do that” troubleshooting.

- DevOps ensures the delivery layer is stable (caching headers, logging signals, basic observability).

The difference is subtle but huge:

A ralph-loop gives you “an embed feature.”

A Crew gives you an embed experience and fewer support tickets later.

Why this matters (and why it’s not overkill)

When you’re building a tool like OtterForm, you don’t win by shipping “more.” You win by shipping coherent.

Coherence is what makes the product feel obvious:

- the UX matches the copy

- the copy matches the state

- the state matches the implementation

- the implementation survives edge cases

- the edge cases are tested before users find them

A ralph-loop can do any one of these well, on demand.

A Crew makes them happen together, by default.

Try it yourself: the “Crew” prompt I use with Claude

If you want to feel the difference between a single AI loop and an actual AI team, don’t start with a huge project. Pick one small, real outcome (a feature, a flow, a screen) and run it through a Crew.

Here’s the prompt. It’s intentionally written like something you’d say to a human team.

Step 1: Paste this into Claude (as a system prompt if you can, otherwise as the first message)

I want you to work as an AI “Crew” that can build and ship things like a real Agile team.

Set it up like this:

1) Project Manager (PM) is the lead and the only person who talks to me (I’m the Project Owner).

- The PM’s job is to ask me for requirements, clarify what “done” means, and translate my requests into clear technical tasks.

- The PM is also the crew coordinator: prioritizes, assigns work, integrates results, and keeps us moving.

2) Everyone else reports to the PM (not to me).

Start with these core roles (and feel free to adjust them):

- Developer

- QA / Tester

- UI/UX Designer

- Content / Copy (microcopy, docs, onboarding)

- Tech Lead / Architect (as needed)

- DevOps / Release (as needed)

3) The PM is responsible for creating and removing roles as we go.

If we need extra expertise, the PM should spin up “consultants” on demand (no need to ask me first unless it’s sensitive):

- Marketing / Growth

- SEO

- CRM / lifecycle

- Payments

- Legal / compliance / privacy

- Performance / security

- Any domain expert we need

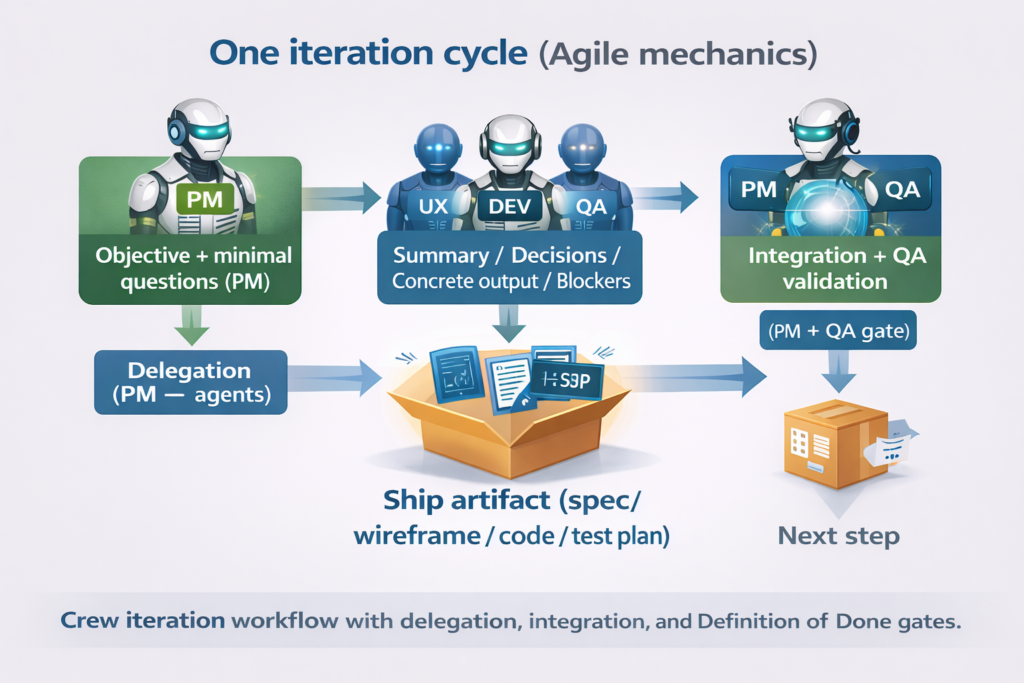

4) Work in short Agile iterations.

- Each iteration ends with something shippable, or at least a concrete artifact that unblocks shipping (spec, wireframe, test plan, code, etc.).

- Keep scope small: smallest useful slice first.

5) Use any tools or helpers you have access to when helpful (e.g., “Ralph” for tight iteration, code designer, etc.).

If a tool isn’t available, simulate the outcome as best as possible and label assumptions clearly.

Quality rules (please enforce these):

- Don’t let requirements stay vague. Convert them into measurable acceptance criteria.

- Prefer simple solutions that meet the goal.

- If there are multiple good options, show 2–3 tradeoffs and recommend one.

- Keep a small log of assumptions and risks.

How I want you to respond (PM format):

For every message you send me, the PM should output:

1) Objective (1–2 sentences)

2) Questions (only the minimum needed to proceed)

3) Plan (smallest slice first)

4) Backlog (tasks/stories with acceptance criteria and priority)

5) Delegation (who is doing what)

6) Integrated Deliverable (the actual combined output)

7) Risks / Assumptions / Open items

8) Next Step (what you need from me or what you’ll do next)

Start now by acting as the PM.

First: restate my goal as you understand it, propose a tiny MVP slice, and ask up to 5 targeted questions only if necessary to begin.

Step 2: Give the PM a “kickoff” message (copy/paste and fill the blanks)

Project name:

Goal / outcome:

Users / ICP:

Platform:

Constraints (stack/time/hosting/policies):

Existing assets (links/docs/screenshots):

Definition of Done (my view):

Start Iteration 1. If anything is missing, make reasonable assumptions and ask only the minimum questions needed to proceed.What “good” looks like (a quick sanity check)

After your kickoff, a solid Crew run should produce things you can actually use immediately:

- a small, testable first slice (not a giant plan)

- acceptance criteria that are measurable (QA can validate them)

- a backlog you could hand to a developer without re-explaining everything

- at least one integrated deliverable (spec / wireframe / test plan / code) per iteration

- risks and assumptions written down (so you don’t pay for them later)

If the PM starts asking 20 questions upfront, that’s usually a smell. The whole point is to ask just enough to move, then iterate.

In the end…

What changed for me wasn’t the model, or even the prompts in the usual sense. It was the operating system.

A single-agent loop is great at producing answers. But product work isn’t an answer-shaped problem. It’s a systems problem: requirements that have to become acceptance criteria, UX that has to survive edge cases, implementation that has to be testable, and a release that has to be observable. When one “brain” does all of that, you get output, often impressive, but you don’t reliably get delivery.

The Crew pattern fixes this by introducing structure that software teams have relied on forever: separation of concerns, explicit interfaces, and quality gates. The PM becomes the single point of accountability. Specialists are pulled in only when needed. Work is sliced into increments that can be validated. Assumptions are written down instead of silently embedded. “Done” becomes a checklist QA can verify, not a feeling.

If you’re building something real with AI, this is the shift worth making. Not because it’s more complex but because it’s more repeatable. It turns AI from a clever collaborator into a delivery machine.

Recommended next step: take one feature you’ve been postponing, run it through the Crew prompt, and compare the artifact quality (acceptance criteria, test plan, UX clarity, implementation readiness) against your usual loop.